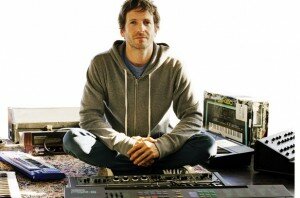

This week NPR’s Morning Edition ran an interesting feature on Lukasz Gottwald (you can listen here). Odds are you do not know who he is but if you listen to pop radio, buy music from iTunes, or spend time around young girls ages 6-13 you’ve heard his music. Currently, the man know in the pop music industry as Dr. Luke has four songs in the top ten, making him the music industry’s hottest producer and, according to Billboard Magazine, “the new Tycoon of Teen.” Dr. Luke is part of the team that has made Katy Perry one of this year’s biggest selling artists and a radio airplay mainstay. Perry’s second solo album, “Teenage Dream,” is currently the top-selling album in the country and the first single from that album, “California Gurls,” has sold more than 3.6 million digital downloads making it second only to Train’s “Hey Soul Sister” (3.8 million) in 2010.

Her whimisical style, over the top-fashion, and spunky lyrics are a hit among young girls. Perry’s album, “Teenage Dream,” is an ode to the highs and lows many teenage girls experience in their social and romantic lives. Her most radio-friendly tunes explore female sexual curiosity (“I Kissed A Girl”) and desire (“Teenage Dream”). Listen to a Perry tune and her voice is a vexing combination of vulnerability, empowerment, and plain fun. A New York Times article back in the summer openly pondered if Perry was a manufactured product or a legit artist. But her digital dominance suggests that she is the real deal in the eyes of what has become one of the pop music industry’s most important consumers, young girls. Dr. Luke tells NPR, “If you look at the charts there’s not a lot of male artists,” adding, “and for whatever reason, female artists sell a lot more records and get played a lot more on the radio.” He’s right. The males that you do see high on the charts–Justin Bieber, Taio Cruz, Usher–appeal more to teenage girls than teenage boys. Even Eminem’s popular single, “Love the Way You Lie,” features another pop singer, Rihanna.

Music industry insiders attribute Dr. Luke’s success to his ability to produce ‘tempo’ tracks that are underscored by catchy melodies and big choruses that come early rather than later in the song. And while this is true his rise in the industry is really a story about how the new media behaviors of the young and the digital, and teenage girls especially, are remaking the pop music landscape. It was teenage girls who made Ke$ha a breakthrough artist and pop star last year. Her hit single, “Tik Tok,” ranks in the iTunes top-ten digital downloads of all-time. It was teenage girls who turned a Disney Channel star, Miley Cyrus, into a pop culture icon. Cyrus’s hit movies, music sales, and sold-out arena tour reveals the downloading and spending power of young girls. Dr. Luke worked on the single, “Party in the USA” that took Cyrus from the Disney Channel, still more of an auditioning ground for pop stardom, to Top 40 radio and mainstream appeal, the true landing spots for pop cred. Dr. Luke even jokes himself about the fact that his songs appeal primarily to young girls. “Apparently my taste is that of a 13-year-old girl,” the thirty-six year old joked recently to Billboard magazine.

Like the music industry in general, Dr. Luke has struck a chord and struck it rich with young girls. The pop music landscape for kids is gendered in some fascinating ways today. Gurl Power is the rule rather than the exception. This has not always been the case. It was adolescent boys who powered hip hop to the top of the charts in the 1990s. And it’s difficult to remember a period when especially young solo performers—think Selena Gomez, Demi Lovato, Vanessa Hudgens, Miley Cyrus—were marketed so heavily by big music labels. How do we explain the “girling” of pop in a Post-Napster music world?

Why is the industry focusing so fiercely on developing tween pop artists often marked by over-produced vocals and cheeky girl empowerment lyrics? And what does this say about the state of pop culture, the new media practices of the young and the digital, and the lives of young girls?

One of the more arresting facts about today’s new media ecology is the degree to which social and mobile media have trickled down to especially young kids, for example, five and six year-olds. Specifically, the impact of Gurl Power in the music industry is mostly attributable to the widespread adoption of mobile media among children. Over the last five years the ownership of mobile media platforms–iPods, phones–among young children has risen sharply. Between 2005-2009 ownership of mobile phones among children between the ages six and eleven years-old increased sixty-eight percent, according to a study by Mediamark Research & Intelligence. Among kids between ten and eleven the increase is even sharper, 80.5%. And then there is the iPod, the real game changer in kid’s new media ecology. When the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted its study of media use in 2004 they found that 18% of young people 8- to 18-years-old owned an iPod/MP3 player. When they executed a follow-up study in 2009 76% of young people reported owning an iPod/MP3 player. I was speaking to a friend recently and he noted that nearly every kid in his son’s second grade class (7- and – 8-year-olds) owns an iPod.

Several factors help explain the heavy footprint of young girls in today’s post-Napster music industry. First, the Generation M2 Report by the Kaiser Family Foundation finds that girls report spending more time with music media than boys across just about every platform—iPods, radio, computers. Second, much of the research, including data we have collected, suggests that boys are more likely to download music illegally than girls. Boys tend to be risk takers and derive great pleasure from challenging authority. This, however, does not mean that girls are submissive in their leisure and pop culture pursuits. The savvy ways that they resist a culture that restricts their freedom of personal expression, mobility and sexuality have been well documented. What we have learned over the last ten years is that these and other restrictions make social and mobile media empowering destinations for girls to write, create, and interact while enjoying the personal and communal benefits of participatory culture.

There is also anecdotal evidence that young girls are drawn to the pop music media experience in ways that are simply more intense than boys, thus socializing them at an earlier age to become consumers of pop music. I call this the “Disney Effect” a reference to the High School Musical, Hannah Montana/Miley Cyrus, Jonas Brothers pop machine that has built an entertainment empire based largely on the tastes, desires, passions, and social communities formed by young girls. The impact of the High School Musical juggernaut in the pop culture world of children has yet to be fully understood. High School Musical (2006) and High School Musical 2 (2007) rocked the pop music charts and signaled young children’s migration to the land of digital music. Within a year of High School Musical’s success Hannah Montana hit the pop scene and further established Gurl Power as a cultural and economic force. Kids downloading music solved one problem for the music industry while creating another one. A generation of children grew up paying for their music rather than seeking out free downloads from peer-to-peer platforms. But even this bit of good news for the industry came at a price: kids are overwhelmingly buying digital downloads rather than albums. Compared to 2009, album sales in 2010 are down more than twelve percent.

Take the pop success of Katy Perry. Though her album “Teenage Dream” topped the album chart the 192,000 units sold during its debut week pales in comparison to the four million digital downloads she has sold. Much to the industry’s chagrin the pop music business model is predicated on digital downloads. Ultimately, that means less revenue and, according to some critics, less artistry. The young and the digital are growing up with a very distinct set of expectations about pop music. If they choose to buy music rather than stream or download from a peer-to-peer platform they are largely interested in digital tracks. All of this, of course, will continue to impact the kind of pop music that is made, packaged, and marketed to young girls.

What girls are doing with pop music in a social media world is something we need to learn more about. Given the inclinations of participatory culture they are likely remaking and remixing Gurl Power in ways that resonate with their own desires and social identities. There must be some measure of personal and collective payoff to seeing young girls occupy a prominent place on the pop culture stage—singing, rocking, and playing instruments. Music camps for teenage girls have become increasingly popular and encourage them to see music as both a creative outlet and a source of personal reflection, empowerment, and expression. But in the corridors of corporate pop music many of the young pop singers reinforce some of the same troubling narratives about girlhood, adolescent romance, and beauty that can produce low-self esteem and unhappiness with their bodies and their lives. Elements of Gurl Power are a classic illustration of what University of Michigan scholar Susan Douglas refers to as “,” that is, the belief that the appearance of female power can be a viable substitute for real social and institutional change. Most of the young pop singers are handled by men and represent what Douglas refers to as the intense sexualization of young girls. And this is not to deny girls their right to explore their identities, sexual or otherwise. But even as Gurl Power targets young female consumers it does so by playing to the gaze and approval of male pop music producers and industry executives.

So we are left to ponder this: Even as Gurl Power surges on are young girls singing, dancing, and, most important, living to a different and, ultimately, more empowering tune?

You can follow S. Craig Watkins on Twitter

last week our group held a similar talk on this subject and you show something we haven’t covered yet, appreciate that.

- Lora